1939 to Kabul: The extraordinary journey of Ella Maillart and Annemarie Schwarzenbach on the eve of the Second World War

It is spring 1939 in Geneva. Europe is wavering between fear and reeling. As the continent moves towards war, two Swiss women get into an open-top car - heading east towards Kabul, Afghanistan.

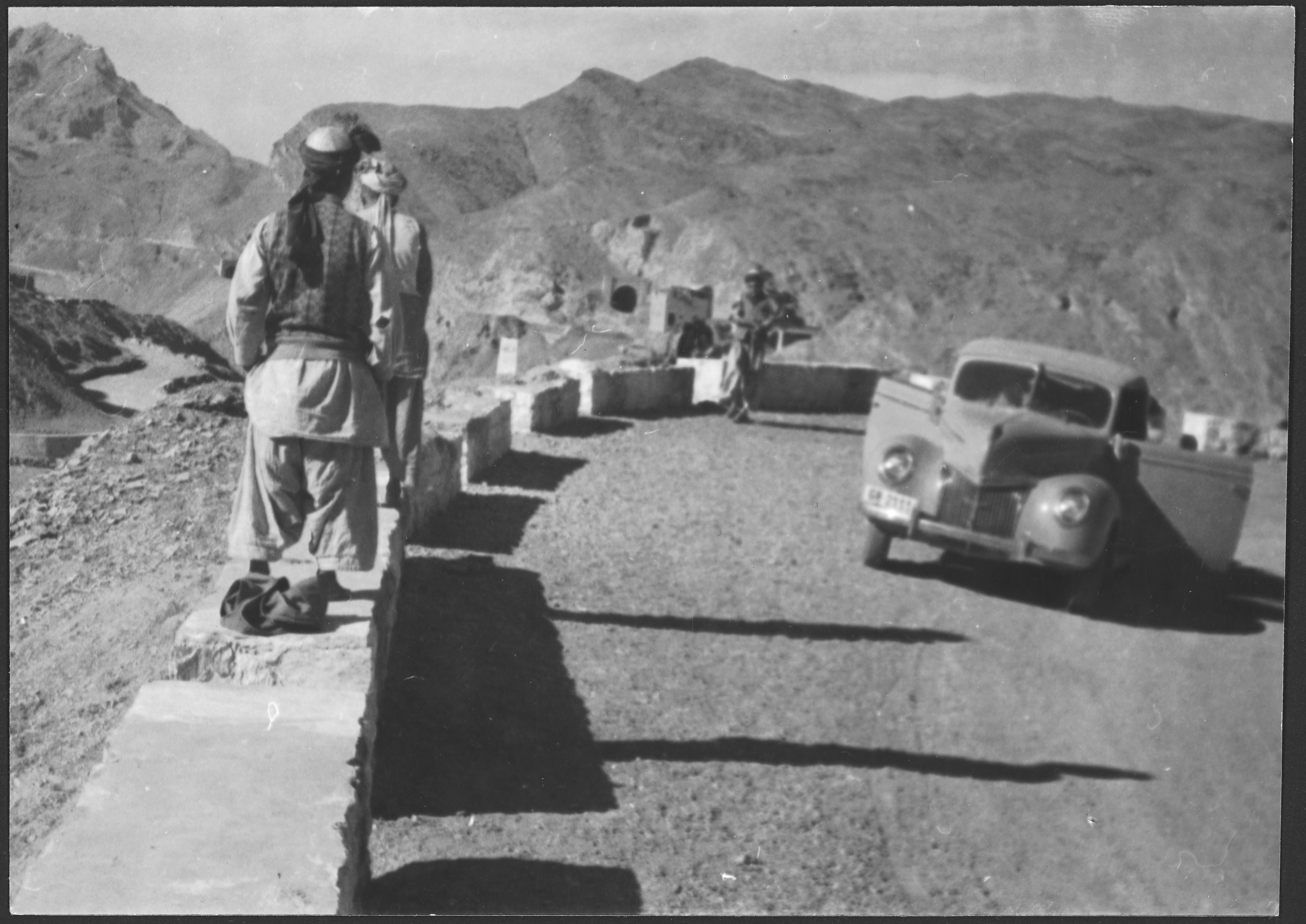

Ella Maillart is 36, an athlete, photographer, travel writer - a woman who asserts her place in the world not through rebellion, but through curiosity. She has crossed the Caucasus on foot, researched in Manchuria, lived in India - and she sees that the world is tilting. Annemarie Schwarzenbach is 31, a style-defining author, photographer, morphine addict - someone who doesn't want to arrive, she wants to disappear. She has crossed America, photographed slums, interviewed workers, written her way through night trains and nervous breakdowns. They set off together in 1939 in a Ford V8 Deluxe Roadster ... Two women, an open-top car, 12,000 kilometers ahead of them, as it turns out in the end. Their destination: Kabul.

Two women traveling alone, without an interpreter, without protection? For many, an affront. For them: a statement.

Annemarie Schwarzenbach - Rebel. Reporter. Voice of a torn time.

Annemarie Schwarzenbach (1908-1942) was many things - and none of them comfortable. Born into a powerful Zurich industrialist family, she was an intellectual, cosmopolitan, anti-fascist, morphine addict, open lesbian, style icon, restless - and above all: one of the first great travel writers of the 20th century. She traveled through four continents: to Russia, to the Congo, to Morocco, to the USA, through the Middle East to Afghanistan and India. But she did not travel to show where she was - but to understand what was. In her photo reportages and literary works, the personal and the political merged in a radically new way. She photographed slums and barricades, wrote about the unemployed in America, nationalists in Europe and women in Palestine. Always with a gaze that took part - but never appropriated.

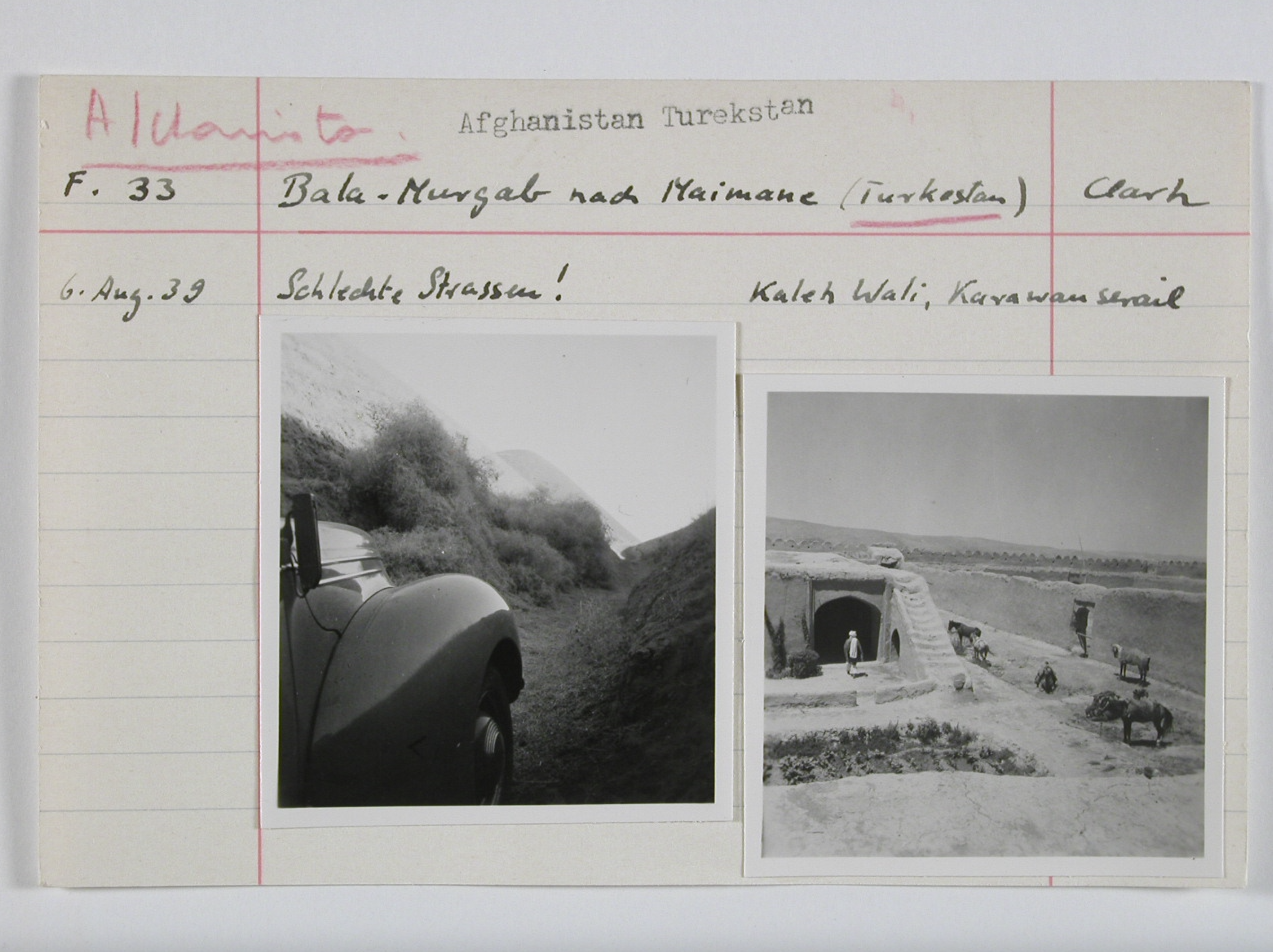

The "Journeys to the Orient" (1933-1939) - through Turkey, Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, Persia, Afghanistan - are considered the center of her work. Hundreds of photographs, reports, letters and autofictional texts were created along the way. Not cold chronicles, but compositions of closeness, pain and reflection. She did not write about the other - she wrote herself into it. Her famous "illustrated index cards" are more than just travelogues. They are small works of art made up of text and images - a play with media, identity and narrative form. They transcend borders: geographical, cultural, linguistic, gender. "Pictures must tell stories," she wrote. And by that she meant: Stories must be more than news. They must show attitude. Even if they hurt. Annemarie Schwarzenbach has transformed traveling into an existential practice. Her work is not a testimony to tourist curiosity - but a chronicle of a seeker who has never stopped asking questions. About the world. About herself. About us.

Ella Maillart - explorer of the human. A free spirit on a global course.

Ella Maillart (1903-1997) was a pioneer - on the seas, in the mountains and in thought. Born in Geneva, she was an exceptional figure as a teenager: top athlete, sailor at the 1924 Olympic Games, founder of the first women's field hockey club in French-speaking Switzerland. A thirst for adventure was not a concept for her - but a way of life. At the age of 27, she traveled to Moscow, crossed the Caucasus on foot and reported on the lives of young people in everyday Soviet life. Shortly afterwards, she was traveling as a journalist in Manchuria - occupied by the Japanese at the time and difficult for Western reporters to access. What drove her was not sensationalism, but a humanistic compass.

Whether in Turkestan, Iran, China, India or Afghanistan - Ella Maillart wanted to understand, not judge. In her texts, one never encounters a colonial gaze, but a deep respect for the other. Her journey with Annemarie Schwarzenbach - from Switzerland to Kabul - was her most famous trip, but only one of many. She later lived in an Indian ashram, where she studied Hindu philosophy intensively - not as a tourist, but as a student. She wrote over a dozen books, which have been translated into numerous languages. But her texts are not travel how-tos. They are invitations to see the world with different eyes. And her photographs? Not accessories. They are statements. Atmospheric, concentrated, full of respect. What makes Ella Maillart so special is her gaze: a mixture of analytical distance and poetic empathy. She didn't just show where she was. She showed how to look. Her texts are feminist - without slogans. Spiritual - without dogma. Political - without ideology. She was a traveler with attitude. And until the end, someone who didn't talk about boundaries, but crossed them.

What is still considered a challenging overland route today was a border crossing in every respect back then. Politically, socially and culturally.

Ella Maillart and Annemarie Schwarzenbach knew each other briefly from literary and intellectual circles in Switzerland, particularly through mutual acquaintances such as Erika and Klaus Mann. There are indications that they had already met before the stay in the clinic, but that a real connection only developed in the winter of 1938/39 through Maillart's visit to Yverdon. In Maillart's book "The Bitter Road", she describes how she visited Schwarzenbach in the clinic - out of a mixture of compassion, curiosity and hope to get her out of her crisis. That's when the real closeness began. You could say that they had already seen each other, but only now did they really recognize each other. Trust grew from this conversation. And from this trust came a plan. Ella wanted to help Annemarie free herself from her addiction - with exercise, with distance, with a journey together. Not as an escape. As an attempt to find herself again.

The Ford and the plan - 12,000 kilometers to Kabul

It is May 1939 when Ella Maillart and Annemarie Schwarzenbach set off in a Ford V8 Deluxe Roadster - two women, an open-top car, 12,000 kilometers ahead of them, as it turns out in the end. Their destination: Kabul. Not because it promises adventure, but because it is far enough away. From Switzerland. From the war. From the pain. The route was not a straight line on the map, but a groping path through a torn Europe and an uncertain East - with detours, delays, wrong turns. This is how the 12,000 kilometers came together, on which they slowly moved away from everything that was holding them back.

The car was a gift from Annemarie's father - a gesture between care and control, perhaps also an attempt to persuade his daughter to return to life. An elegant convertible, built for boulevards - and yet ready to become the stage for an exceptional journey. They drive off, without fanfare, without escorts, without a mission. No sponsors, no mission. Just two women in search of direction.

The route takes them through Austria, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey. Over the Taurus Mountains, on through Syria, Iraq and Iran. Over the Elburs, past Tehran, to Herat. And finally to Kabul.

They sleep in guesthouses, with friends, in the open air. Repairing tires, organizing provisions, negotiating with border officials. Maillart documents with precision and restraint. Schwarzenbach's writing is melancholy and existential. In many areas there are hardly any paved roads - often just tracks in the dust. And two women traveling alone, without an interpreter, without protection? For many, an affront. For them: a statement. What is still considered a challenging overland route today was a border crossing in every respect back then. Politically, socially, culturally.

The trigger for the trip was pragmatic: when Schwarzenbach received the Ford, Maillart suggested the trip to Afghanistan - an idea somewhere between a cure and a challenge. Six months, financed by reports and pictures. Schwarzenbach took the wheel, arranged visas and insurance. Her diplomatic passport opened doors. They set off on June 6, 1939. They reached Kabul at the beginning of September. Not like heroines, but like two people who were looking for more than just a destination.

The journey was demanding. The Ford broke down several times. Schwarzenbach broke down mentally and turned to morphine again. Maillart hoped for redemption through movement - but there was no solace in the distance, only confrontation.

Kabul, September 1939 - The world is burning - and they are right in the middle of it

The world caught up with them in Kabul: War had broken out. Europe was in flames, France and Great Britain had declared war on Germany. What began as a journey of self-discovery suddenly became an escape route. Political reality was closer than any border post - and left no more time for illusions.

What began as a departure ended abruptly. Annemarie fell ill and became addicted to morphine again. Ella realizes that movement does not heal. The desert gives nothing - it only exposes. Maillart travels on to India. Schwarzenbach stays behind, struggles with himself, with withdrawal, later travels alone over the Khyber Pass to Lahore and returns to Europe.

What remains - not a road trip, but a legacy

The friendship breaks up quietly, but the experience remains. In 1947, Maillart's report "The Bitter Road" is published, in which she describes Schwarzenbach under the name "Christina". It is only decades later that Annemarie's voice is heard in all its depth.

In 2024, their joint legacy is added to the UNESCO Memory of the World Register. Not because of the track. But because of the attitude. Because they set out when the world was falling apart. Because they showed what it means to really be on the road.

"I'm not traveling to escape - but to look," said Ella. And Annemarie wrote: "I travel to remember." Her journey was not a road trip. It was a manifesto - for freedom, for friendship, for searching.

One Life. Live it.

Photos: Swiss National Library, SLA-Schwarzenbach